books, 2008

In 2007 a major gas pipeline was laid across south Wales that would, it was claimed, provide 20% of Britain’s gas needs. As part of an artist-led residency supported by Safle and Brecon Beacons National Park, I chose to document the effect of the pipeline construction on a small wooded dingle at Penpont near Brecon and by coincidence, this same small wood also became the site of an anti-pipeline protest camp in January 2007. Between January and June 2007, I invited local people, anti-pipeline protesters, Brecon Beacons National Park employees, National Grid employees, contractors and security guards to talk to me in a small hut that I installed in the dingle. Not everyone was keen to participate and nobody involved with the pipeline construction would agree to talk to me. In June 2007, police and sheriff’s officers evicted the protesters from the wood and steel mesh fencing and 24 hour security guards were placed around the dingle and the adjacent pipeline works. Along with other local people, I was forbidden to enter the dingle (under threat of arrest) until October 2007.

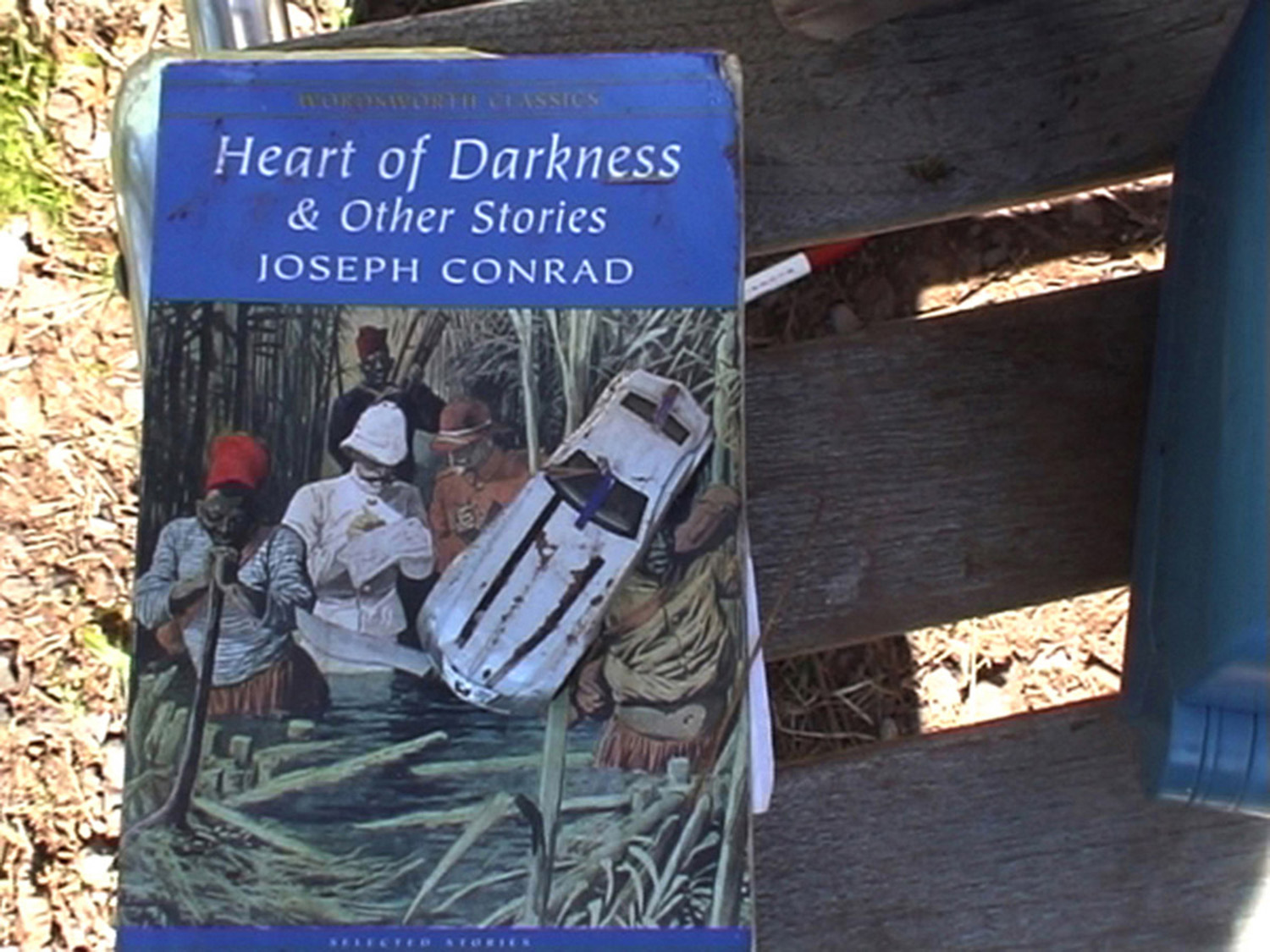

People talked to me in the hut of their feelings about nature, their feelings about current environmental policies and their feelings about the future. I mentioned my interest in science fiction as an expression of contemporary anxieties to the vicar of Penpont Church and discovered that as well as being an Anglican priest, Reverend Neil Hook writes books on science fiction. He told me that Rachel Carson had included a science fiction story at the beginning of her influential 1962 book, Silent Spring, that warned of the negative impact of modern society on the environment. In the hut in the dingle, one person told me that reading Silent Spring as a teenager had helped to shape her view of the world. Books was a slide and sound installation in the hut in the dingle that was off the grid and powered only by sunlight. In talking to people in the hut, I was interested in the relationship between people’s private thoughts and dominant socio-economic structures. The people who chose to talk to me in the hut had a sense of freedom to say what they wanted that others perhaps did not share, constricted as they were by their roles or jobs. Protesters told me that they were often criticized for being lazy, though in many ways it was not easy living in a makeshift camp in the wood. I was struck by the fact that they had time to read books, discuss issues and creatively put together structures and assemblages.

In science fiction, books are sometimes seen as a challenge or alternative to dystopian worlds: for example, in 60s new wave cinema:

When seeking sources which critiqued contemporary thought, science fiction was a rich seam to be mined. Examples include Truffant’s 1966 film Fahrenheit 451, based on the dystopian novel by Ray Bradbury, set in a world where books are forbidden and critical thought is proscribed.(1)

In Fahrenheit 451, people critical of a society that is dominated by large, flat-screen and interactive televisions go to live makeshift lives in a wood, as it is only there that they have the freedom to read and memorise books.

(1) Professor Mark L. Brake and Reverend Neil Hook, Different Engines, How Science Drives Fiction and Fiction Drives Science, Macmillan, London, New York, 2008, pp. 157-60.