eden, ty pawb, 10 august - 29 october 2019

Eden, was commissioned for Ty Pawb’s exhibition PLAY-WORK, celebrating play and Wrexham's radical adventure playgrounds. Developed in collaboration with playworkers, the installation shifted and changed as children played. The exhibition received close to 10,000 visitors over a ten-week period.

eden, 2019

The playworkers create a large adventure playground in the gallery. Using hundreds of pallets, they build vertical and hollow structures and cover the floor with sand. They are militant about the children’s right to do what they want and they worry that I am going to be precious about my installation. I reassure them that the children’s freedom to deconstruct and reconstruct is what excites me about the work. I explain that the blue tent that framed my own childhood experience of collecting, playing, immersion, will be the starting point of my installation but the tent’s form will be low and triangular like the tent in Hélio Oiticica’s 1969 Whitechapel installation, Eden. Oiticica (1969) remarked that ‘I had the idea of appropriating those places I liked, real places where I felt alive’ and compared his installation to ‘a map of my imagination … you go into.’(1)

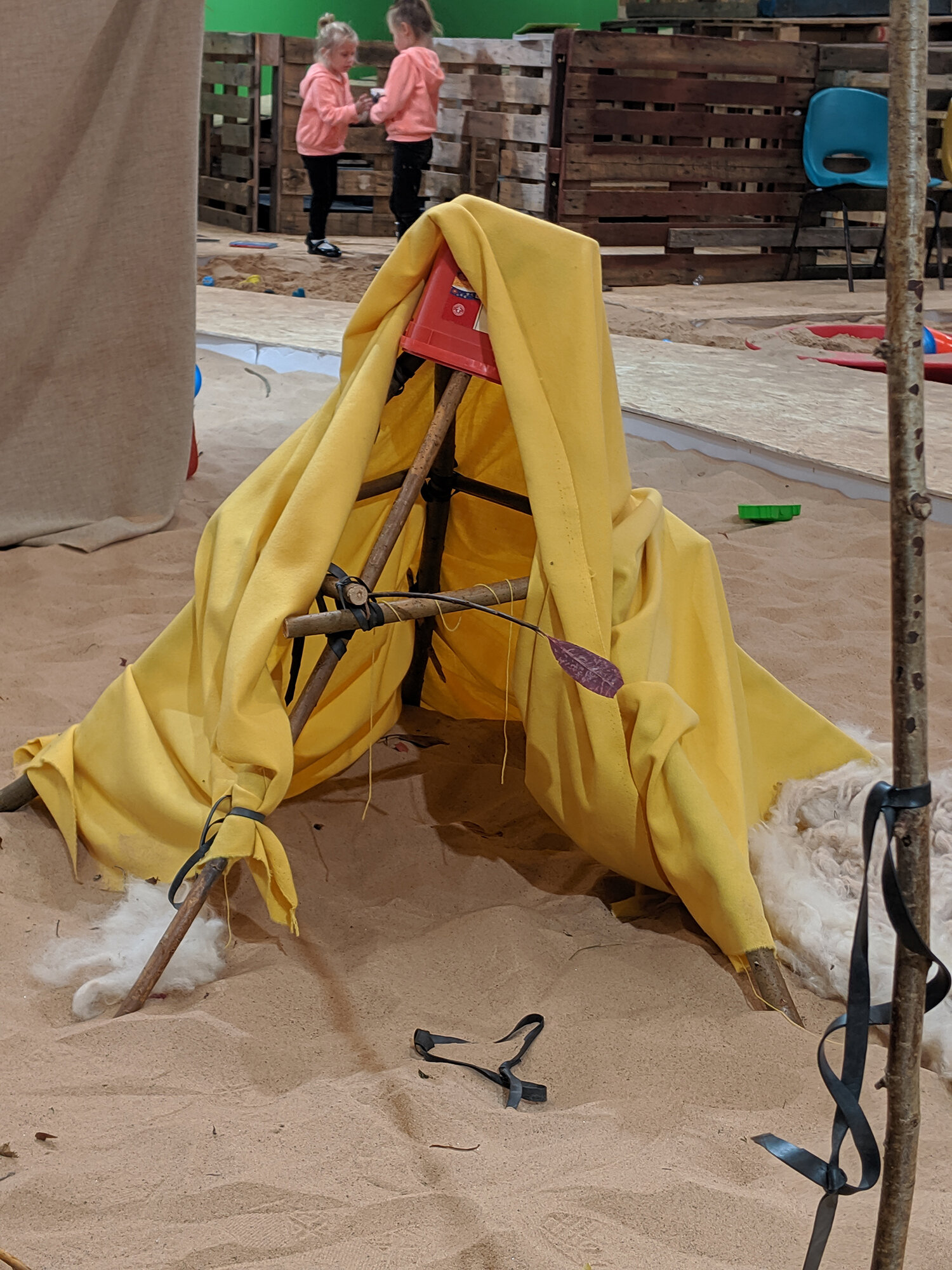

I originally propose to make geometric shapes in modular kit form so that the children can take them apart and reassemble them but I can see that the playworkers are unimpressed. They feel this is too prescriptive for the children and does not fit with the playwork ethic of using recycled or waste materials as ‘loose parts’. Following our discussions, the materials that I use in the final installation include hazel and willow sticks, strips of recycled inner tube rubber, raw wool fleeces and lengths of Welsh flannel. Due to the intervention of the playworkers the structures are soft and makeshift looking rather than taut and modernist in form. One of the first things the children do is to bust out the corners of the rectangular shapes. One of the playworkers tells me that they always do this: that they need to have ‘through routes’ when playing. With its open ends and stronger triangular form, the blue tent survives for weeks and nearly to the end of the exhibition. Of the rectangles, the taller one, is toppled almost immediately by the children and the materials are quickly repurposed.

Children and teenagers love the sheep fleeces, which are dragged into dens and chillout zones and act as soft landings when the children do flips and jumps from the pallet structures. Children, families, parents and grandparents hang out in the playground during the summer holidays when it is manned by professional playworkers. A group of young adults with learning disabilities take turns to jump from the highest pallet structure as the others cheer and whoop.

I love the fact that the playworkers are so militant about the ethos that drives their professional practice: an ethos that ultimately derives from modernist practice via 1930s design, the junk playground, British postwar reconstruction and now, surviving austerity, is activated in an art gallery. I discuss Hélio Oiticica’s idea of ‘feeling participation’ with the playworkers. One of them tells me that she knows she is ‘old-fashioned', but she will never give up on the values of playwork. I feel confused because I sense that what the playworkers are doing in deprived wards of post-industrial Wales is still cutting edge, best practice, avant-garde. Since 2010, Wales has initiated a Play Sufficiency Duty: the only country in the world to have done this. I think about the Bardsey Island boatman and fisherman, Colin Evans’ suggestion that young people are not learning through doing. It feels good to celebrate and be part of this living social practice where children are physical, take risks, play and learn with full autonomy.

During the course of the exhibition, I take regular photos of the changes that take place and I speak with the playworkers manning the exhibition. I see the various components turn into snakes, flags, vehicles, cooking places and endless dens. A red leaf, which I had placed in the original installation but which had long been buried in the sand, resurfaces as a delicately placed ‘lever’ for a yellow space rocket. At the end of the exhibition, I visit one last time. The children have rebuilt the structures into one big shelter. It reminds me of a multi-coloured maloca and the first word that comes to my mind is ‘communal.’ It has more internal possibilities than the tight structures I gave to the children. It is as if the materials have been ‘let go’. There are more planes and edges, almost like fractals. What emerges through the children’s mutual enjoyment of play is ‘spontaneous coherence’ or amans (love). Humberto Maturana and Ximena Yanez suggest that amans fundamentally drives evolutionary processes.(2) Conversely, loss of autonomy and intimacy experienced by the child can detrimentally be conserved and accepted in daily life as “something that is culturally legitimate”.(3)

(1) Brett, Guy; Oiticica, Hélio. Hélio Oiticica Retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery, until April 6: Oiticica talks to Guy Brett. Studio International, London, v.177, n.909, p.134, mar. 1969.

(2) H. R. Maturana, S. R. Munoz, X. D. Yanez, Cultural Biology: Systemic Consequences of Our Evolutionary Natural Drift as Autopoietic Systems, Foundations of Science, 21(4), 2015.

(3) Humberto Maturana and Gerda Verden-Zoller, The Origin of Humanness in the Biology of Love, Exeter, Imprint Academic, 2008, pp. 5-6, 98-9.